It has been a few months.

Other day Chris asked me, “where are some posts lad?” To which I had no response save professing a newfound fear of the keyboard.

‘˜Course he didn’t believe me. “You use a freakin’ keyboard all the time,” he says. I make no argument; I could proffer that I have to use one more than I’d like, but utter nothing aloud, the Fear impeding my breathing.

Wait, seems I’m pecking these dirty white keys at this exact instance. “Send me a hard copy,” mutters Seibold, “it will receive proper burnination.”

I’m afeared of burnination -‘“ Seibold slings this threat amongst his neighbors and righteously asserts his dominion over the neighborhood swimming hole. They are afeared as well. Passionately afeared.

After a slight pause I fumble a few adieu words.

“Just like Pruno’¦.” I think I hear, huh? “Yeah, Pruno lad,” clearer now, “no worries see, tap out a few phrases, Finnegans-style let ‘˜em sit a few days, go from there’¦it’s not just the fermentation it’s the INGREDIENTS.”

“For some really, really good Pruno,” Chris deadpans, “dump it all into the swill’¦ Pruno.”

Quietly I return the phone to its cradle.

Sunday past was only slightly breezy in the early hours; a nipping wind rustling frost-stiff grasses sparkling hopeful predawn glimmers of a sky that would soon lay heavy a dense blue fever of monotonous hue breaking the seeping graycloud lethargy and forcing the malaise of late Fall into a hampered sidethought.

The destination for the morning was to take me in the neighborhood of fifty miles northward to the geography that formed the original passageway for colonial westward expansion: the Cumberland Gap.

The Gap itself is a rare geological break in the Cumberland Mountain chain of the lower Appalachians that is large enough to have been significant as a useful thoroughfare back when just ripping an asphalt road over a mountaintop wasn’t quite an option. Wide enough for herds of bison to weave through, the Cherokee walked silent paths through the Gap to the pastureland of southern Kentucky.

This is the land of Daniel Boone’s notoriety; in the early 1770’s he was the first to explore the vicinity and scout the tangles of endless trees. Following his lead settlers hacked their way through the Gap expanding the old forest routes into the famed Wilderness Road, haevily pounding their way into the pastureland of Kentucky in greatest numbers between 1775 and 1810. The Cherokee, it seems, were not pleased. (Shawnee, I think also, top-of-me-head.)

On this day the past trickled around my consciousness, competing with the rolling sound of a near creek pouring swiftly from a limestone cavern on the cliffside just behind where I stood in dead sunlight.

I struggled to imagine animal trails through the heart of the Gap, but could only hear the distant rumbles of Highway 25-E as it charged into the nearly mile-long, four-lane tunnel that bores its way straight through the mountain from Tennessee into Middlesboro, Kentucky. Completed in 1996 the tunnel was a means to both dispose of the old highway that once scrawled the distance through the Gap and a means to return the Gap itself to a “natural” state, manifest historicity, as maintained by the National Park Service, full of natural plentitude, devoid of mechanistic incursion. Why go over a mountain when you can tear right through it?

The incipient “forest” replenished to the Gap is beginning the painfully slow journey of restoration that will never be seen to us in this life. This gave it all the unauthenticity of a sterile city park replete with extra wide gravel walking trails; although numerous ridge trails coursed ruggedly following along old pathways from the Civil War, passing by rifle trenches filled in from a hundred and forty-or-so years of decaying vegetation and shifting hillside. At one ridge apex sat a small wood-top covered concrete pavilion marking the intersection of three states: Tennessee, Kentucky, and Virginia, right here in the domain of the Gap, weathered blue signs facing the partial views toward the bright vistas of their respective states, a cupric colored USGS benchmark marking the exact point of convergence as it calmly erodes into history.

There are many more trails though, the Park lists around seventy or so miles of hiking to horse multi-use trails extending, I’m guessing to the northeast and southwest along the Cumberland Mountains. The road from the lowland trailheads twists severely up the Gap’s northeastern mountainside revealing a view from the Pinnacle, a touristy park and walk-yer-lazed-arse convenience pull-in that leads hungry observers to a panoramic overlook of a mostly southern expanse of distant, wavering terrain; a place of serenity belying its prominence as a military observation stronghold during the Civil War. To the northwest Fern Lake reflects lazy sunlight amidst the sagging peaks of the Cumberlands, slowly dripping the water bounty to the city of Middlesboro.

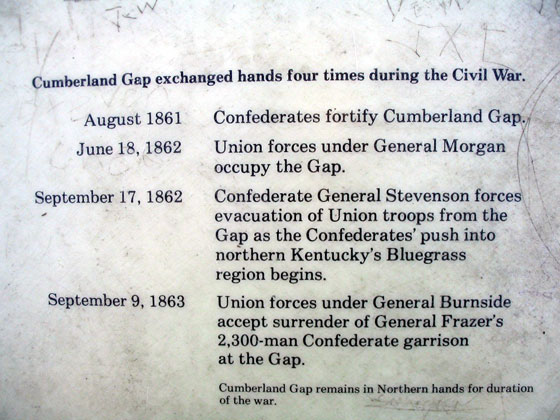

At the Pinnacle remnants remain of war past. The geology of the Gap made it a virtual fortress – Union and Confederate soldiers alike occupied the surrounding terrain; hoping to gain a significant advantage that never would be as worthwhile as perceived. Civil War cannons perch solemn on remoulded wheel-housings etched with countless insignia and initials of modern fools unable to respect the dead, history, or something transcendent of Self. Respect and Reflection are virtues barren and neglected by forthright omission in the seething idiocy of many that visit these places of dying importance. But we all too shall fade in rust and ash.

And as voices fade so do the inscriptions albeit sometimes more begrudgingly. I was enlightened to find along the high rocks of the ridgeline a carving, slight fading yet distinct, but remarkably a match of the date of the final Confederate surrender from the sign (PIC) above: September 9, 1863.

As I scraped away debris and plucked dead summer grass I could see the year emerge plainly and distinct in the west-falling sunlight: 1863 looking chiseled almost but ten years prior. The soldier’s name and regiment were there too but faded shallow; it was obvious from the rock that the date I had mostly unearthed had been protected as found, somewhat in a state of partial burial and recovery, for the carving was near a main trail and likely encountered by many over a stream of decades and I feeling somewhat the more serene given that my birthday is September the 9th although timed far distant ‘“ ahead exactly one hundred and eleven years from the time these marks were carefully laid in stone.

Although I hesitated to find significance, maybe a small divination, I decided that a little benign coincidence easily feeds my perplexion, especially giving a decent one in three hundred and sixty five shot or so of correspondence.

As I left the Gap that day I was filled more with imagery of people than I often get when in the Great Smokies; although the nature of the Smokies seems more extrusive in the capacity of anthropology, it is not as dynamic and has resisted a potentiality of change that almost condemned it to the human-wrought obedience of the Gap; but the Gap is very different and I haven’t the experience and understanding there to shape it in reflection just yet.

But the Appalachian microverse dies ill at ease here as it does throughout my land. Split-rail fences still stand defiantly against time and culture; waiting to be forgotten on high ridgetops; rottings to the soil-covered limestone and sandstone pinnacles that will far outlast the brash carvings of unaware humankind.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.